bangkokpost.com

Clustered Story

Bangkok Post - The gist of Thai politics over 20 years

bangkokpost.com · Feb 19, 2026 · Collected from GDELT

Summary

Published: 20260219T184500Z

Full Article

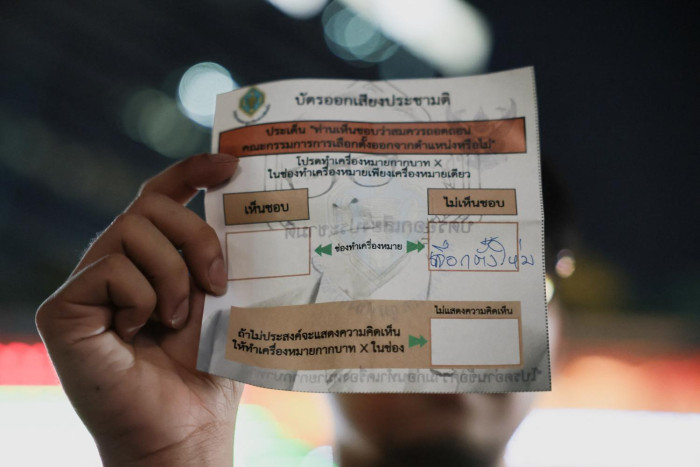

A protester holds up a marked ballot bearing the word 'reelection' during a mock referendum calling for the dismissal of members of Thailand's Election Commission (EC) in Bangkok on Feb 15. The EC has faced mounting pressure over alleged irregularities and a lack of transparency in vote counting in more than a dozen constituencies following the Feb 8 general election. (Photo: Reuters) Thailand's democratic institutions have been repressed and kept weak to the point that confusion still prevails almost two weeks after the Feb 8 election, which purportedly showed a clear victory for the ruling Bhumjaithai (BJT) Party under Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul. On the one hand, Mr Anutin and BJT stalwarts are busy forming a coalition government with other parties. On the other hand, fraud allegations from civil society groups and the opposition People's Party have reached a critical mass with the plausibility that the recent vote might be nullified to pave the way for a new poll.The Election Commission (EC) has clearly made missteps in overseeing the election. There have been alleged discrepancies between ballot papers and vote tallies, and dubious counting and vote-reporting procedures. Most glaring is the questionable QR and bar codes on the ballots that could be traced to individual voters in violation of the constitution, which mandates privacy and confidentiality. At issue is whether these infractions and flaws resulted from sheer incompetence and gross negligence or deliberate and systematic efforts to game and control election results. In either case, the EC has lost public trust and should be held fully accountable. Critics raise doubts and accuse that BJT's 193 parliamentary seats out of 500 overcame the People's Party by a large margin of 75, which also suggests that any deliberate vote fraud would have to be rampant and widespread. Once a mid-sized party, BJT just won 71 seats in the previous election in 2023. In Thailand, where leaks from official circles are commonplace, whistle-blowers would not be hard to come by if there were such massive vote fraud. In any case, as the contested election process works its way to the Constitutional Court, it would be surprising to see a nullification verdict. After 20 years of volatility and turmoil in Thai politics -- characterised by coloured street protests between yellows and reds, two military coups and multiple judicial interventions -- the conservative establishment believed to be behind BJT has finally won a decisive poll victory. If BJT is able to proceed in forming a government with coalition allies, there is likely to be establishment-backed political stability for the first time in two decades. The onus would then fall on BJT, and Mr Anutin would address economic doldrums and mend Thailand's deep divide. But if economic growth thins further below two percent per year while corruption and graft thicken, an anti-establishment backlash could bring about a reckoning between the old guard clinging onto privileges from the past and the new generations clamouring for a better future. Up until the latest poll, the conservative establishment faced two major movements for progress and reform. The first was Thaksin Shinawatra and his juggernaut Thai Rak Thai Party, which won 248 of 500 assembly seats in the 2001 election. Prior to Thaksin, Thai political parties had been weak and beset with party hopping, patronage networks, pork-barrelling, and graft. The "money politics" of vote-buying in elections, accompanied by corruption among elected politicians, resulted in periodic military coups, once every seven years, since 1932, when the first of 20 constitutions was promulgated to end absolute monarchy. Thaksin's Thai Rak Thai party convulsed the establishment by connecting directly with voters through "populist" policy innovations, such as universal healthcare, debt relief, and microcredit schemes, alongside industrial policies that put Thailand on a strong growth trajectory and regional leadership in the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis. He set a record for completing a full term in 2005 and won re-election with 377 seats under a one-party government. As Thaksin's popularity with the masses expanded, royalist yellow-shirt street protesters attacked his business conflicts of interest and paved the way for a coup that routed and exiled him in 2006. Over the next 20 years, including anti-establishment red-shirt demonstrations, his brother-in-law, sister, daughter, and two proxies became prime minister and were ousted either by the military or judiciary. Along the way, a new generational challenge came to the fore under millennials and Gen Z, who want to regain a future they lost from years of protests and coups. Under the Future Forward and Move Forward parties, this movement for institutional reforms of the monarchy, military, bureaucracy, and business oligopoly initially came in third in the 2019 poll but then won the 2023 election. Both were opposed and obstructed from government formation by the Constitutional Court, the election and anti-corruption commissions. As with the Thaksin parties, these new-gen parties were duly dissolved, and their core leaders were banned from running for office for ten years. The beneficiary of these power plays is BJT. It has more than doubled its seats from 2023, having risen to power on royalism, militarism and nationalism, owing to the Thai-Cambodian border clashes in July and December last year. In addition to Mr Anutin's nationalist fervour, BJT also campaigned on technocratic professionalism, represented by Commerce Minister Suphajee Suthumpun, Finance Minister Ekniti Nitithanprapas, and Foreign Minister Sihasak Phuangketkeow. To what extent these technocrats are given a free hand, and how many old-style patronage-driven politicians occupy the new cabinet, will determine its ability to boost growth and limit corruption. Perhaps Thai voters got tired of two decades of political tumult and wanted to give stability and the status quo a chance. But the electorate also passed a referendum to draft a new constitution to replace the 2017 charter from the military era, in search of near-term solutions and longer-term structural change at the same time. That the People's Party won all of Bangkok's 33 constituencies and 31 of 100 from the proportionally represented party-list suggests the main opposition can still make a strong comeback in the next election. Over two decades, BJT's backers have succeeded in holding Thailand's political stability and economic future hostage while seeing off two critical challenges from Thaksin's populist and redistributive agenda and deep-seated structural reforms advocated by the People's Party and its precursors. Thailand's powers-that-be have been nifty and nuanced in keeping opponents divided and continually weakened by military coups, judicial dissolutions and long bans, shrewdly assisted by custodian agencies until its loyalists could utilise nationalism and popular fatigue to win office, undeterred by long-term costs to the country from low growth, lack of competitiveness, and diminished international standing. Thitinan Pongsudhirak Senior fellow of the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University A professor and senior fellow of the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University’s Faculty of Political Science, he earned a PhD from the London School of Economics with a top dissertation prize in 2002. Recognised for excellence in opinion writing from Society of Publishers in Asia, his views and articles have been published widely by local and international media.

Share this story