dmnews.com

Scientists found rotator cuff tears in nearly all adults over 40 and say were overtreating them

dmnews.com · Feb 22, 2026 · Collected from GDELT

Summary

Published: 20260222T003000Z

Full Article

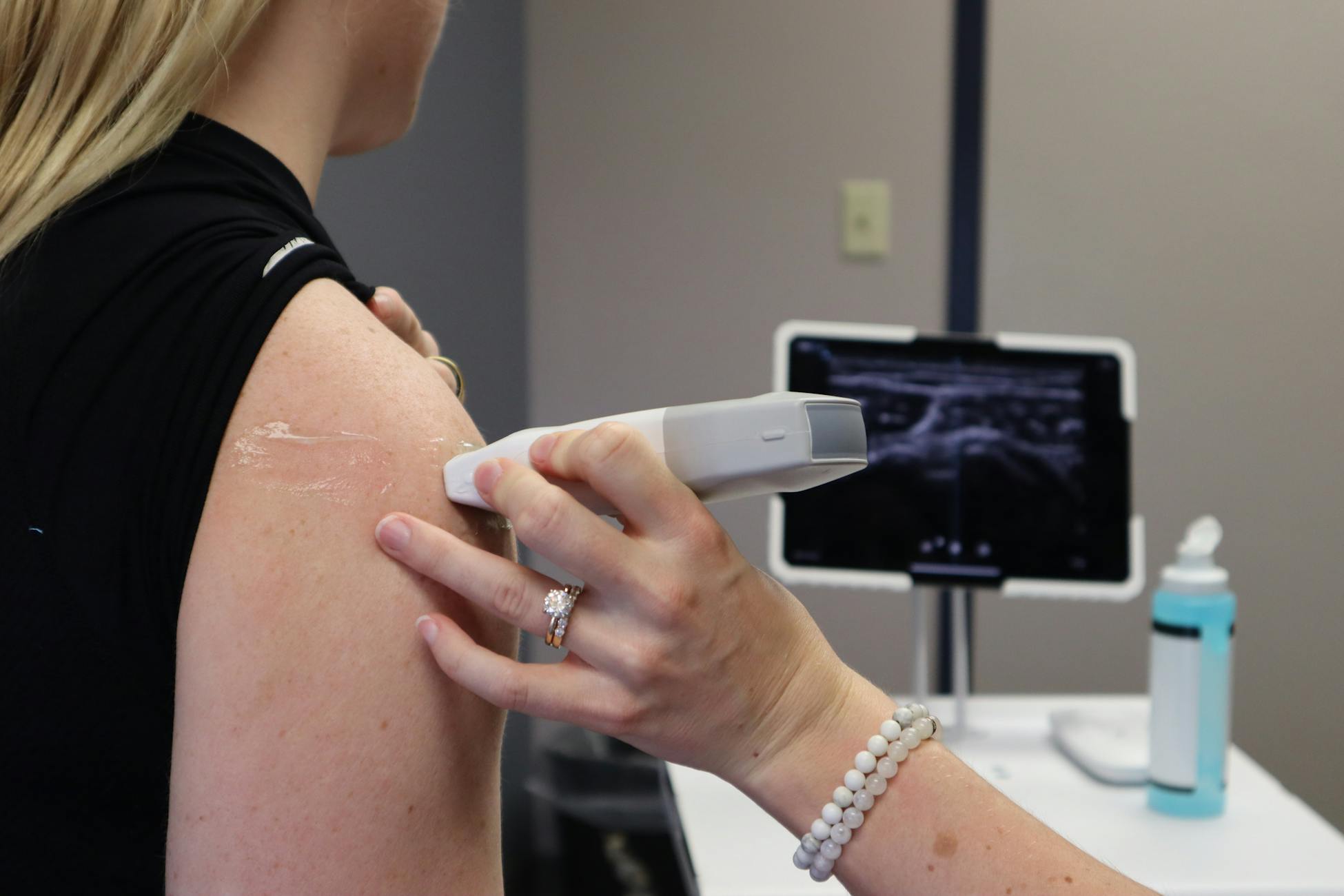

Add DMNews to your Google News feed. Tension: Rotator cuff abnormalities appear in nearly all adults over 40 on MRI, yet the medical system continues to treat these findings as pathology requiring intervention — a contradiction that suggests the problem may not be in the shoulder, but in the scan. Noise: Imaging technology has outpaced clinical understanding, creating what researchers call a diagnostic-therapeutic cascade — where the mere visibility of anatomical changes triggers treatment protocols designed for genuine injuries, not age-related wear. Direct Message: The real issue is not overdiagnosis of shoulders but a medical culture that conflates seeing something with needing to fix it — and until clinicians, patients, and insurers reckon with the difference between an anatomical finding and a clinical problem, millions of people will continue receiving surgeries for a condition that is, by the numbers, simply what it looks like to age. To learn more about our editorial approach, explore The Direct Message methodology. Something peculiar happens when a person over 40 walks into an orthopedic clinic with shoulder pain and is sent for an MRI: the scan almost always finds something wrong. A partial tear. A frayed tendon. Fluid where fluid perhaps should not be. The physician points to the image, the patient sees the damage, and a treatment pathway — often surgical — begins. But a growing body of research now suggests that what the scan reveals may not be a problem at all. It may simply be what a shoulder looks like after four decades of use. That is the deeply inconvenient finding emerging from recent studies: rotator cuff abnormalities are so prevalent in adults over 40 that they appear to be a near-universal feature of aging, not a medical condition requiring repair. And if that is true, then a significant portion of the shoulder surgeries performed each year — an industry worth billions globally — may be treating anatomy, not pathology. The tension is stark. Medicine has spent decades refining its ability to see inside the human body with extraordinary precision. But the capacity to detect has, in this case, dramatically outstripped the capacity to interpret — and the consequences land squarely on the patient. The scale of the finding is difficult to dismiss. Research evaluated by Medical Dialogues has drawn attention to studies demonstrating that rotator cuff abnormalities — including partial-thickness tears, tendinosis, and supraspinatus fraying — are present in the overwhelming majority of adults over 40, including those with no shoulder pain whatsoever. Asymptomatic individuals, scanned for research purposes, showed the same structural changes that clinicians routinely cite as justification for surgical intervention in patients who do report discomfort. This is not a fringe observation. A body of literature stretching back more than a decade has consistently shown that the prevalence of rotator cuff tears on MRI increases with age in a pattern that mirrors other degenerative changes — grey hair, reduced skin elasticity, disc dehydration in the spine. By the time individuals reach their sixties and seventies, full-thickness tears are common even in the absence of symptoms. What researchers describe as the diagnostic-therapeutic cascade — the chain reaction in which a scan reveals a finding, which triggers a diagnosis, which triggers a treatment plan — is at the heart of the concern. Once an MRI shows a tear, the clinical machinery is difficult to stop. Patients, understandably alarmed by the image of a torn tendon, often consent to procedures they might not need. Surgeons, trained to repair structural damage, follow protocols designed for traumatic injuries rather than age-related wear. As The Eastleigh Voice reported, experts have begun stating plainly that most shoulder abnormalities found on scans in adults over 40 do not require surgery or treatment. The message is direct: the presence of a tear on imaging does not, by itself, constitute an indication for intervention. Yet the conventional narrative — the one patients encounter in most clinical settings — remains stubbornly unchanged. Shoulder pain leads to imaging. Imaging leads to findings. Findings lead to recommendations. And the recommendation, more often than clinical evidence supports, is surgical repair. The economics of this pattern are not incidental. Rotator cuff repair is one of the most commonly performed orthopedic procedures in the developed world. In the United States alone, hundreds of thousands are carried out annually, generating substantial revenue for surgical practices, hospitals, and device manufacturers. The incentive structure — in which doing more is reimbursed and watchful waiting is not — reinforces the cascade at every step. This is what health economists sometimes call the incidentaloma problem, borrowed from radiology’s experience with incidental findings on CT scans. When imaging technology becomes sensitive enough to detect changes that are clinically meaningless, the system faces a choice: recalibrate its understanding of normal, or continue treating every finding as if it demands action. In the case of rotator cuffs, the evidence suggests that medicine has largely chosen the latter. Research published in Cureus has examined national imaging guidelines for rotator cuff assessment, particularly in the context of shoulder dislocations in adults aged 40 to 60. The findings raise questions about whether current protocols — which frequently recommend MRI as a matter of course — are calibrated to clinical need or simply to the availability of imaging technology. When nearly every scan in this age group returns an abnormal result, the diagnostic value of that result approaches zero. There is an important distinction that gets lost in the noise. Traumatic rotator cuff tears — caused by a fall, a sudden impact, or an acute injury — are genuinely different from degenerative tears that accumulate silently over years. The former often do require surgical repair, particularly when accompanied by significant functional loss. The latter, which constitute the vast majority of tears found incidentally on MRI, frequently respond to conservative management: physical therapy, activity modification, anti-inflammatory measures, and time. The problem is that the MRI does not reliably distinguish between these categories. A tear is a tear on the image. Context — the patient’s history, the mechanism of onset, the degree of functional impairment — must do the interpretive work that the scan cannot. And in a system that privileges the visual certainty of imaging over the slower, more ambiguous process of clinical judgment, context often loses. Researchers have given this dynamic a name: the visibility trap. The more clearly a technology can reveal anatomical detail, the harder it becomes for clinicians and patients alike to accept that what they are seeing may not matter. The image feels like evidence. The tear feels like a verdict. And the surgery feels like the only rational response — even when the data suggest otherwise. The implications extend well beyond orthopedics. The rotator cuff finding is a case study in a broader phenomenon reshaping modern medicine: the gap between what technology can detect and what clinical science can meaningfully interpret. The same dynamic plays out in prostate cancer screening, thyroid nodule biopsies, and spinal imaging for back pain — domains where overdiagnosis and overtreatment have been extensively documented but have proven remarkably difficult to curb. What makes the shoulder particularly instructive is the sheer ubiquity of the finding. When a condition is present in nearly every member of a population, it ceases to be a condition. It becomes a characteristic. The failure to update diagnostic frameworks accordingly is not merely an academic oversight — it is a structural problem with real costs, measured in unnecessary surgeries, post-operative complications, prolonged recoveries, and the psychological burden of being told one’s body is broken when it is, by any population-level standard, entirely normal. There is also a subtler cost, one that falls within the domain of how people relate to their own aging. When a 45-year-old is shown an MRI of a partially torn supraspinatus and told it needs repair, the implicit message is that the body has failed — that something is wrong that must be fixed. The alternative framing — that the body is changing in ways that are expected, manageable, and compatible with a full and active life — is rarely offered with equal conviction. The psychological consequence is a form of what might be called medicalized fragility: the internalization of normal aging as disease. The emerging consensus among researchers is not that rotator cuff surgery should be abandoned. It is that the threshold for recommending it should be dramatically higher than current practice reflects — anchored in functional impairment and failed conservative treatment, not in the mere presence of a tear on a scan. The evidence base for this position is substantial and growing. Trending around the web: Psychology says the reason some people become more beautiful with age while others seem to harden comes down to one thing. Whether they kept their curiosity or traded it for certainty - The Vessel If someone does these 8 things without being asked, they were probably raised by a mother who did everything alone - The Vessel If someone keeps choosing you after seeing your worst side, they love you in a way most people never experience - The Vessel But changing clinical practice requires more than evidence. It requires confronting the economic incentives, the patient expectations, and the professional culture that sustain the current approach. It requires physicians willing to tell patients that the tear on their MRI is not a diagnosis. It requires patients willing to accept that not every visible abnorma

Share this story